I think nearly every soapmaker makes a mistake and winds up with lye-heavy soap. I unmolded these beauties this morning. This soap was supposed to be a really nice lavender goat milk soap. I’m not happy that I used some nice materials with this result, but it does happen.

I unmolded these beauties this morning. This soap was supposed to be a really nice lavender goat milk soap. I’m not happy that I used some nice materials with this result, but it does happen.

I knew something was wrong as I was mixing this soap together. It seemed to trace much more quickly than I thought it would, and I wondered if it was false trace, so I kept blending. I am still not sure if it really did get mixed well.

I check on my soap frequently as it sits to gel, and this one acted up almost immediately. I could see a yellow fluid oozing out of the tops of the bars. And it kept oozing, even after I patted it dry with paper towels. I checked it several more times, and each time, more liquid ooze.

It also seemed to take quite a long time to begin to gel. A few hours passed before I detected the temperature was over 100°F. It also seemed softer than usual. Even if soaps haven’t yet begun to gel, they begin to harden so that you can press lightly on the surface.

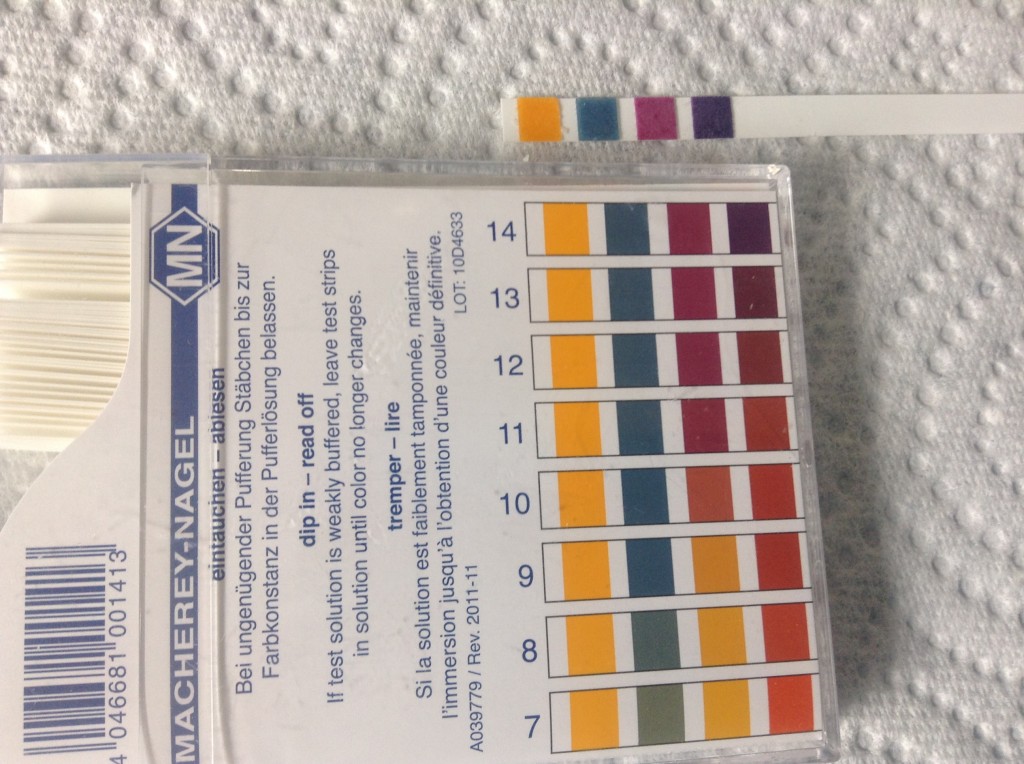

Sure enough, when I unmolded the soaps this morning, there was a large amount of that yellow liquid underneath the bars. They were the mottled shade you see in the image rather than a nice uniform lavender shade. I could see the lye much better on the bottoms of the bars, so out of curiosity, I put a pH strip into some of the oozy liquid on the bottom of a bar.

If you haven’t used these kinds of test strips before, you might not be familiar with how to read them. Essentially, you hold the strip up to the scale on the package above and compare it to the different sets of colors. I think my test strip looks most like the set labeled 14. If you are not familiar with the pH scale, it works like this:

If you haven’t used these kinds of test strips before, you might not be familiar with how to read them. Essentially, you hold the strip up to the scale on the package above and compare it to the different sets of colors. I think my test strip looks most like the set labeled 14. If you are not familiar with the pH scale, it works like this:

- It ranges from 0-14.

- It measures how acidic or basic (or alkaline) a substance is.

- Substances with a pH below 7 are acidic.

- Substances with a pH above 7 are alkaline.

- Substances with a pH of 7 are neutral and are neither acidic nor alkaline.

- Each number is ten times greater than the number before. For example, something that is pH 11 is ten times more alkaline than something that is pH 10. Likewise, something that is pH 4 is ten times more acidic than something that is pH 5.

- 14 is just about as alkaline as you can get. Lye is about 14 on the pH scale.

Yikes! I certainly should not have been handling my soap with bare hands! It was dangerously lye heavy. I immediately washed my hands. The tips of my fingers are a little dry, but other than that, no damage. A quick note: The soap itself was probably not uniformly pH 14. I’m pretty sure the pH strip came in direct contact with a patch of lye in the soap. In any case, I should have been using gloves to unmold. I’m really glad I didn’t try to zap test it.

In the case of this particular batch, I don’t know what I did wrong, so rebatching it in an attempt to fix it is probably not a good idea. If you know exactly what you did wrong to produce lye heavy soap, you can try rebatching it and correcting the problem. For instance, if you know you forgot an oil, or that you used the wrong amount of oil, you can shred the soap with a grater and put it in the crock pot, add the oil, and cook the soap, similar to making hot process soap. I personally hate rebatching. Your rebatched soap is just not going to be as nice as regular cold process or even hot process soap. I have done it once and swore I’d never do it again. However, some soapmakers regularly rebatch their soap and like it just fine.

What can you do if you don’t know what you did wrong? You have two options:

- Toss it in the trash.

- Use it as laundry soap.

I put on a pair of gloves and shredded the soap. Then I put it in a box in the laundry room. Interestingly enough, the first soaps used were laundry soaps. Ancient Babylonians used soap as early as 2800 BCE. Archaeologists have found evidence of a soap-like residue in containers, and a cuneiform tablet dated from 2200 BCE had a soap recipe on it. The recipe describes the soap’s use for washing clothes. Your grandmother or great-grandmother may even have made soap to use for the laundry. Though lye-heavy soap is too harsh to use on your skin, you can use it to clean your clothes, and that way, at least it doesn’t go to waste. Lye-heavy soap is actually pretty good at whitening whites and cutting grease. It’s best used with some washing soda, Borax, and baking soda to create a nice detergent. The Soap Queen has some laundry soap tips here.