Do you ever read over recipes or watch soaping videos and wonder why soapmakers use the ingredients they use? After all, the only essentials for a good bar of handmade soap are oils, water, and lye. However, certain additives do impart some nice qualities to your soap, and in a series of posts, I wanted to share some of the “extra” ingredients I use in soap and why I use them.

Heavy cream has a lot of fat in it—36% fat or more. Goat milk typically has 4-5% fat. Cream is very rich and smooth. While the benefits of milks—especially goat milk—are widely known, not as many soapers use cream, possibly because of the expense. I wouldn’t try substituting all of the water in a recipe with cream, and not only because of the cost, but also because of the high fat content. The cream will likely congeal fairly quickly, even if you freeze it first, because the lye will react to the fat in the cream. If you have made milk soaps, you may have noticed that if you set the milk and lye mixture aside for a few moments, it does start to thicken as the lye reacts to the fats in the milk. Another reason you might not want to use cream as a total water replacement is that the high fat content might really throw off your superfat percentage.

So how do I use cream in soap? I usually add about 4-5% of the amount of oils to a batch of soap. So, for example, if I make a batch of soap that is 500 grams (I always measure in grams; it’s more precise than ounces and easier to convert), then I would add about 22 grams of cream to the batch. I admit this is approximate because I usually add a round number of grams of cream to my soap. For example, my typical batch is about 2.5 pounds of oils, or 1120 grams, and I usually add about 50 grams of cream to a batch that size. I would recommend using heavy cream at a rate of about 3-5%. You really don’t need to use a lot. When I use cream in my soap, I remove the same amount of water from the recipe. For example, in my batch with 50 grams of cream, I remove 50 grams of distilled water from the recipe. If you use full water and cream, you might find your soap takes a little longer to harden. I have not experimented with using full water and cream.

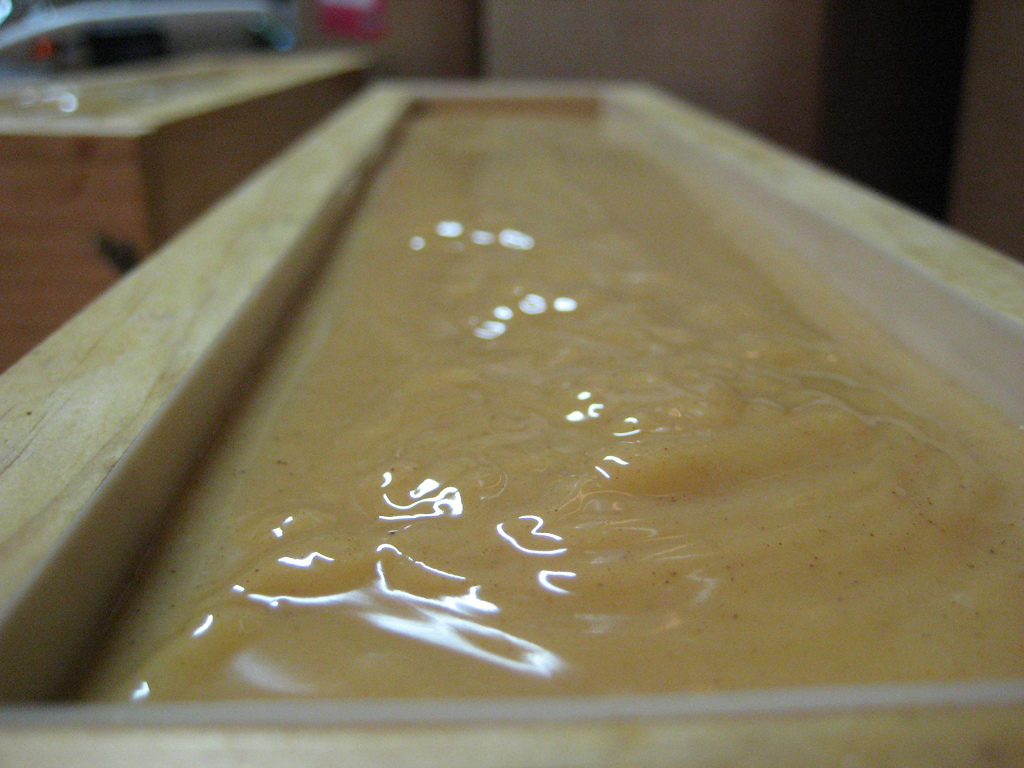

Before I add the cream to the oils, I warm it up a bit so that it is the same temperature as the oils (more or less). Then, I add my cream directly to my oils and stick blend it before adding the lye. I have noticed that it will not emulsify completely with the oils. Typically there are tiny white flecks of cream floating on the top of my oils. I usually give the oils one more quick stick blend before adding the lye water, but it probably isn’t necessary because once the lye water is added, it will all blend.

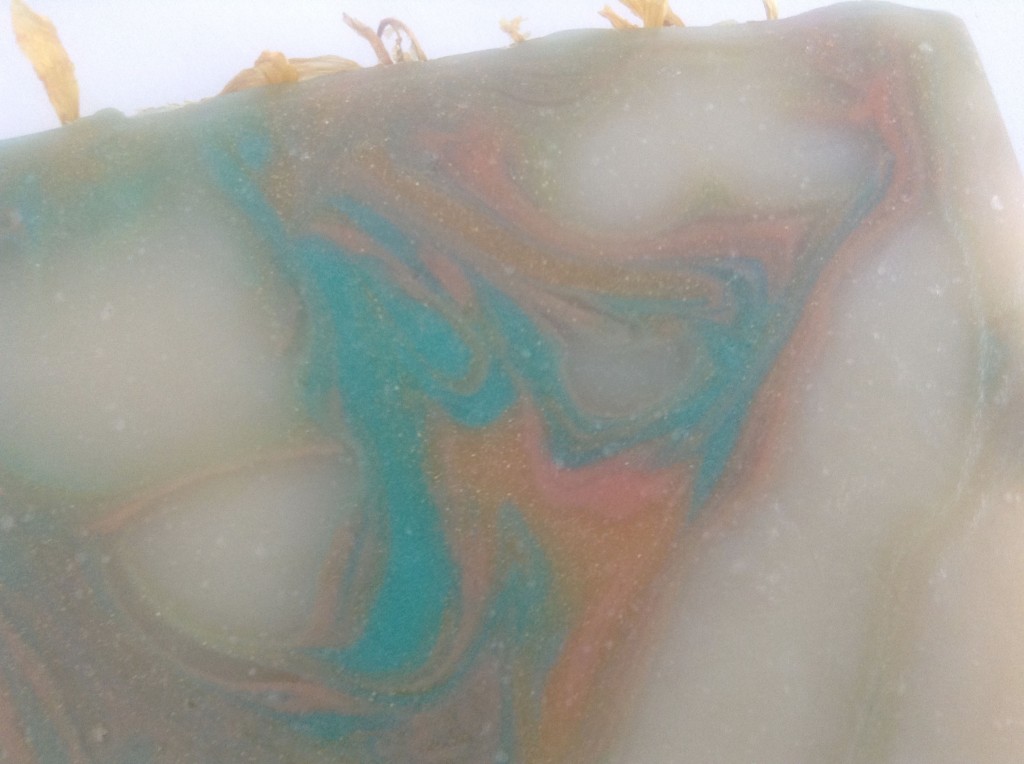

I first noticed the benefits of using cream in soap by accident. I made a batch of Creamy Coconut soap with coconut milk and cream.

I mainly added the cream because I felt it would be in keeping with the name of the soap to have both real coconut milk and real cream in it. When I used it in the shower, I noticed how smooth the bars felt. If you can believe it, I didn’t immediately realize this smoothness was because of the cream. I thought it might have been the coconut milk.

I started noticing that other soapmakers used cream in their soaps, and when I ordered soaps from these soapmakers, I noticed how smooth their bars were. At first, I wasn’t sure why their soaps were so much smoother than mine either because there are so many variables—oil recipes, other additives, and the like. But eventually I realized it was the cream in the soap that added smoothness. I have used cream in almost all of the soaps I have made since that discovery (I typically do not use it in milk soaps, with the exception of Creamy Coconut).

In addition to smoothness, cream adds some of the same benefits as other milks in soap—extra conditioning being the main benefit imparted by heavy cream. I mainly enjoy the feel of soap with cream in it. It is definitely smoother than soap made just with water. It feels silky on the skin. I typically do not have to use much lotion at all because of the conditioning oils and butters in my soap, but I have noticed even less of a need to use lotion in those soaps made with cream.

Adding just a little bit of cream can add some great qualities to your soap. With my recipe of just 50 grams, I am adding 18 grams of fat, so my superfat percentage will not be drastically different from my calculation.

As usual, David Fisher has experimented with cream and shared his results. You can see what will happen if you add lye to cream in his tutorial. I personally have not found it necessary to freeze the cream I use in my own recipes. In addition, I have never noticed any discoloration as can happen when you use goat milk in place of water. I actually haven’t tried using just a small amount of liquid goat milk and adding it directly to the oils as I do with heavy cream, so you might find that solution works just as well for you.

- 151 grams distilled water

- 63 grams lye

- 203 grams olive oil

- 113 grams coconut oil

- 112 grams palm oil

- 22 grams castor oil

- 20 grams heavy cream

- 23 grams fragrance or essential oil

- Dissolve the lye in the distilled water and set aside to cool.

- Melt coconut oil and palm oil.

- Add olive oil and castor oil to melted hard oils.

- Add heavy cream to oils and blend.

- Combine lye water with blended oils when both reach about 100ºF. The temperature doesn't need to be exact, but it should be close.

- Blend with stick blender until you reach trace.

- Add fragrance or essential oil and stir well until thoroughly combined.

- Pour into a mold, cover mold with plastic wrap, and drape with towel. One pound of oils will make approximately 1.4 pounds of soap.

- Let soap go through gel phase and saponify for about one day before unmolding.

Note: you can substitute coconut milk, like I did, for the water simply by using 151 grams of frozen coconut milk and slowly adding the lye to the milk until the lye is dissolved. You can also use colorants. I have not had issues with this soap overheating or acting strangely in gel phase, but keep and eye on it, and remove some insulation if it appears to be getting too hot. Also, you can opt not to gel this soap and instead put it in the freezer overnight. The cream might make the soap heat up in the refrigerator, so it might need the additional chill of the freezer to prevent gel phase if you choose not to gel.

I completely scrapped my other recipe. I used two ounces of carrot baby food, removing two ounces of water from my recipe and reduced the total amount of liquid in the recipe from 38% (which

I completely scrapped my other recipe. I used two ounces of carrot baby food, removing two ounces of water from my recipe and reduced the total amount of liquid in the recipe from 38% (which